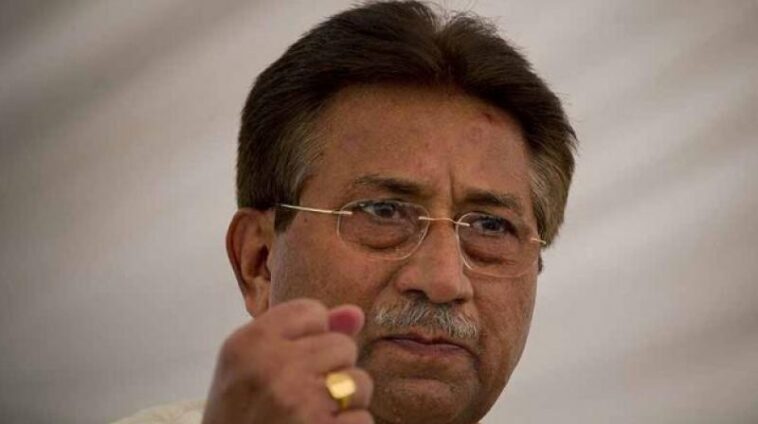

Gen. Pervez Musharraf, the former Pakistani president and CEO

Once we were all out of uniform, I also encountered several people in fruitless attempts to broker peace. However, Gen. Pervez Musharraf, the former Pakistani president and CEO, was the person I most wanted to see. I wanted it for two distinct reasons. It all started with his strategy and the part he played as the head of Pakistan’s army in starting the Kargil War in 1999 and then letting others finish it off. A fundamental tenet of battle is “Surprise and Deception,” and Musharraf was a passionate student of the subject. He lied to the highest degree during the Kargil War, but the problem was that he lied to his own side (the political establishment and the other two services of the Pakistani military forces) more than he lied to the enemy (Indian Army). I never got the chance to meet him, but if I had, I would have asked him to explain the presumptions he made in 1999 when he planned to make the Indian Army leave the Siachen Glacier. Why was the Siachen Glacier so important to him? Few people have looked over his career to make reasonable deductions.

The second reason I wanted to meet Musharraf was that we both graduated from the Royal College of Defence Studies (RCDS) of the UK Defence Academy in London, which is the oldest and maybe best school in the world for teaching strategic studies and international politics. Of course, we attended the programme over a far longer period of time than you did. The opportunity to talk with him about a lot of other subjects has also passed with his untimely passing. Pervez Musharraf controlled Pakistan during some of the most turbulent periods in the subcontinent, therefore it is only fitting that I share some of my insights regarding his life and times.

In India, Musharraf is widely reviled for the needless deaths of 527 Indian soldiers in a conflict he started and thought he could win. They were in defensive posture, so their deaths were obviously lower, but at least 450 Pakistani soldiers were also slain. Musharraf’s military acumen may be called into doubt in any discussion, and the execution strategy, including combat initiation, would infuriate any tactician. However, Musharraf’s obsession with fighting India throughout his time as head of Pakistan’s armed forces was motivated by two factors. The first was that he was originally a Mohajir in a Punjabi-dominated Pakistan Army, despite his daring exploits as an SSG officer and commander. The Pakistan Army’s racial and religious differences are enthrallingly incredible. Even if the same is categorically denied, they nonetheless exist. There have been numerous Mohajir Pakistan Army commanders, but Musharraf aimed to elevate his “Pakistaniat” a little above the rest. During the renowned “Bus Yatra” goodwill visit by the Indian Prime Minister in February 1999, his refusal to acknowledge Atal Behari Vajpayee came across as immaturity. For them to remain in their haughty positions of power, they required symbols of hatred, and Musharraf was prepared to go above and beyond to make that happen. Intriguingly, the Pakistan Mujahid unit’s commanding officer (CO) saluted me impeccably and vigorously when I crossed the ageing bridge to the PoK side during the first flag meeting in many years at Uri’s Kaman Post (now called Kaman Aman Setu) in February 2005. At the time, I oversaw the Uri Brigade. Musharraf might have been as responsible as the CO, for sure.

When the SSG made the decision to devise a strategy to send his Northern Light Infantry men to take the Indian Army’s winter-vacated defences in the Kargil area, his overly intelligent intellect helped him maintain his equilibrium. As a result, the Pakistani artillery observation stations would have the opportunity to see the travelling convoys from Srinagar to Leh, which are also the lifeline to Thoise, the base for Siachen’s logistics, and disrupt them. He had hoped that this would interfere with India’s capacity to supply Leh and Thoise for the winter because the second route, Manali-Upshi-Leh, only had a short window of time when it was open. It was a strategy that was hardly ever wargamed. These are national decisions requiring the deployment of national resources; they are never made based on the whims and past experiences of a senior commander. Musharraf wanted to surprise the Pakistani public by announcing that the Pakistan Army would be occupying the Siachen Glacier under his direction and planning by the end of 1999 or the start of the new millennium. A part of the strategy was to force the Indian Army’s formations and units to relocate from the Kashmir Valley to Kargil, creating a pathway for widespread infiltration into the Valley.

Also Read: | Bengaluru: 2 first-time passengers attempt to cross electrified Namma Metro tracks, delay trains on Green Line

Musharraf could have tried this elsewhere, but he was too preoccupied with Siachen. By just six days in April 1984, the Indian Army had defeated the Pakistani Army in the race to seize Siachen and the Saltoro Range, which served as its guardian boundary. Musharraf made many attempts to get a foothold on the Saltoro Range while serving as an SSG brigadier at the time, but in vain because the Indian Army was deeply entrenched there. His mentality was affected by this setback. He extrapolated from this failure his prediction that the Indian Army would also fall short in its attempt to drive his soldiers off the Kargil heights. Musharraf was not the Pakistani hero he wanted to be recognised as because history had other predictions for how the Kargil war would turn out.

The underlying fact that the Pakistan Army has never formally admitted to its people or to the political leadership its inability to acquire even a foothold on the frightening landmark means that the Siachen phenomena is rarely known to the general public in India. The reality is that because of the shelter provided by the Saltoro Range, the Pakistan Army is unable to view the Siachen Glacier, which led Musharraf to make a number of decisions. It would have been wiser to have acknowledged that rather than try to start a conflict in Kargil. That would have truly occurred, and Musharraf’s place in history might have been more revered.