Jobs data released on Friday indicate that job markets have recovered, the unemployment rate has decreased, and the percentage of jobs in agriculture has decreased, which are positive economic indicators for the government prior to the 2024 national election.

In May of last year, when the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) released GDP figures for 2021-22, it was evident that the Indian economy had surpassed pre-pandemic levels in terms of total incomes, following a 6.8% decline in 2020-21. During that time, it was still unknown whether the pandemic had left enduring scars on the labour market. The 2021-22 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) report released by the NSO on February 24 indicates that even the labour markets have recovered from the pandemic, based on its key findings. Two significant statistics provide support for this conclusion. In the 2021-22 PLFS round, the unemployment rate has decreased further, and more critically, the increase in agriculture’s employment share seen in the 2020-21 round has been reversed.

Certainly, the most recent PLFS results are not entirely unexpected, as the quarterly PLFS bulletins – which, unlike the annual report, only cover urban labour markets – have been pointing to an improvement in labour market indicators. While the aforementioned statistics unambiguously indicate improvement, the data’s fine print reveals persistent fault lines that reflect an unequal recovery in labour markets.

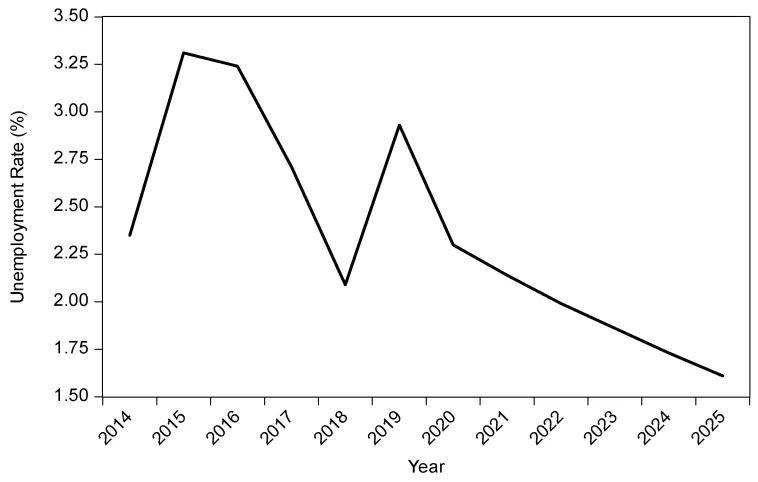

According to common perception, the unemployment rate is the most important indicator of labour market distress or absence thereof. The latest PLFS report, which covers the period from July 2021 to June 2022, will provide the Narendra Modi administration with much cause for celebration in this regard. The annual unemployment rate in 2021-22 was the lowest it has ever been since the publication of the first PLFS report in 2017-18, at 4.1%. When the first PLFS was published in May of 2019, it revealed that the unemployment rate for 2017-18 had reached a four-decade high of 6.1%. While the government insists that PLFS reports – which are the official source of employment-unemployment statistics in India – cannot be directly compared to the Employment Unemployment Surveys released by the NSSO in the past, unemployment rates have been lower in previous EUS reports.

Another encouraging statistic for the government is that the decline in the unemployment rate is not due to a significant number of individuals leaving the labour force. The Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR), which measures the proportion of the working-age population that is employed or actively seeking employment, has declined marginally between 2020-21 and 2021-22, but is still higher than levels observed in pre-pandemic PLFS cycles.

The most significant statistical evidence of the pandemic’s effect on labour markets was a paradoxical increase in the agricultural employment share of total employment in 2020-21. This number increased from 42.5% in 2018-2019 to 45.6% in 2019-2020 (the final quarter of the survey was impacted by the strict first closure of the pandemic) and to 46.5% in 2020-21. This statistic’s anecdotal explanation was straightforward. As the lockdown compelled urban workers to return to their villages, they had no choice but to labour on their farms (or face disguised unemployment). The 2021-22 PLFS report indicates that some migrants who had returned to their villages have returned to the cities, with agriculture’s share falling to 45.5%, just below the level seen in 2019-20, but still higher than in 2017-18 and 2018-19.

Despite the fact that the PLFS provides documentary evidence of this trend, economists have been pointing to it for some time. “As lockdowns were lifted, urban employment returned. Workers who had returned to their homes during the pandemic returned to the major urban centres… In a February 16 research note, HSBC economists Pranjul Bhandari and Aayushi Chaudhary stated, “By the end of 2022, the return of workers to urban India would be nearly complete, as would the resulting growth stimulus.”

Do these statistics suggest that the Indian labour market has never been stronger since 2017-18? A year before the general elections of 2024, this is as much a political question as it is an economic one.

A HT analysis of the numbers’ fine print indicates that India’s labour market may have abandoned its quantitative scars, but it still displays qualitative bruising. In 2021-22, the percentage of unpaid family employees (a category of self-employment) reached 17.5%, 4.2 percentage points higher than in 2018-19, the last annual PLFS round without the pandemic’s influence. Similarly, while the 2021-22 round demonstrates a slight increase in the proportion of regular wage and salary workers, this proportion is still lower than it was prior to the pandemic.

The numbers in the most recent PLFS report appear to validate the government’s economic strategy of a calibrated withdrawal from the distress mitigation welfare policies, including the provision of free food grains and increased expenditure on MGNREGS. Whether or not this strategy achieves its political goals in 2024 will depend on two key factors: the extent of headwinds that the global slowdown and dissipation of domestic pent-up demand generate for the Indian economy, and the performance of this year’s monsoon, which will be crucial for the rural economy in the run-up to the 2024 elections.